Reading Sole Thickness

Q: Hello Pete,

Is there an accurate

way to estimate the thickness of a horse’s sole?

A: Very good question! 20 years ago, I was

actually trained to trim the sole until tiny dots of blood appeared (and I still

see people doing this today). I soon realized that when blood appears, you have

already trimmed at least a half-inch too far—removing all of the horse’s natural

protection of the sensitive corium of the foot. When trimming a horse’s foot, we

should

always be careful to leave this

1/2- to 3/4-inch-thick layer of protective sole, but we must also remove any

excess to allow the foot to be as compact as possible to maintain agility. This

means that estimating sole thickness is crucial to competent trimming and

shoeing.

Important Note: The

very best you can do is no more, and no less than an estimation! When in doubt,

or if the situation is critical, always get radiographs to be sure. That said,

even when the highest-quality radiographs are available, it is really only

possible to measure sole thickness at a small part of the sole that is in

profile in the image. Additionally, the radiograph shows the sole thickness only

during the moment in time (in the past) that it was taken—so the estimation of

sole thickness is still important.

The first and most important step in estimating sole

thickness is developing an understanding of the shape of the internal

structures. The “foundation” of the

front-half of the foot is bone—the

foundation of the back-half is flexible cartilage. Together, they form the

shape of a miniature hoof with a concaved sole. Covering this bone and cartilage

“foundation” is a 3/8th-inch-thick sock-like layer of live, vascular,

nerve-filled tissue (see figure 1). This layer—the corium—must always be

well-protected.

Cadaver specimen.

This is how the horses’ foot looks with the “skin” (hoof wall, sole, bars and

frog) removed. All of this highly-sensitive tissue must be covered by at least a

1/2-inch-thick protective layer for the horse to be safe and sound. If the

slightest bit of blood is drawn during a trim, a significant error in judgment

was made—not a slight slip-up. Photo reprinted from the book Care and

Rehabilitation of the Equine Foot, P. Ramey.

The shape of these internal structures can vary. Some

horses may have slightly more or less concavity of the solar surface. Other

horses—particularly past founder cases and horses with upright or “club”

feet—may have a remodeled coffin bone, altering this shape at the toe area. This

is why radiographs remain important, even for highly-skilled estimators of sole

thickness. But most horses will have a general shape and form very similar to

the Figure 1. Looking at this picture, take special note of the area between the

frog corium and the sole corium. This area forms the collateral grooves—the

“seam” between the frog and sole that you typically clean out with a hoof pick.

The collateral grooves are important for sole estimation because in a normal

hoof, the sole material in the bottom of the groove rarely varies in thickness.

The very deepest part of this groove tends to be 3/8th-inch away from

the corium (live tissue) whether the rest of the sole is too thick or too thin.

This means that from one end to the other, the collateral grooves along the frog

are quite accurate for locating the

sensitive tissue. Exceptions: When

subsolar abscessing has been present, the collateral grooves may be farther from

the corium. Fungal and/or bacterial infections may erode them closer or all the

way into the corium. Always be prepared to fall back on radiographs when

conditions of the foot are abnormal.

So putting it all together so far, if 1) you know how the

internal structures are shaped, and 2) you know where they are within the foot,

it becomes pretty easy to estimate the thickness of the sole in any area of the

foot.

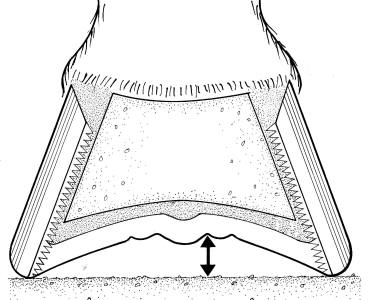

To use this insight in the field, be sure that there is

always enough sole material (in the outer perimeter adjacent to the white line)

to lift the collateral grooves at least ½-inch (or more) off the ground. This

can be measured by picking up the foot and laying a rasp across the foot—in any

direction, depending on which part of the sole you are evaluating. Measure from

the rasp to the bottom of the collateral groove with a thin ruler (see Figure

2). The groove should generally be left deeper in the back of the foot (heel

height is a separate and complex subject) and the sole at the toe should never

be trimmed so that the collateral groove at the apex of the frog is less than

½-inch off the ground—5/8ths-inch is even better, plus any additional lift

provided by hoof wall extending past the sole.

Proper placement of rasp and ruler to estimate the thickness of sole in the

areas where the rasp has been placed. If the measurement to the bottom of the

groove is 1/2- to 3/4-inch, there is probably a correct amount of sole covering

the internal structures. Photo reprinted from the book Care and

Rehabilitation of the Equine Foot, P. Ramey.

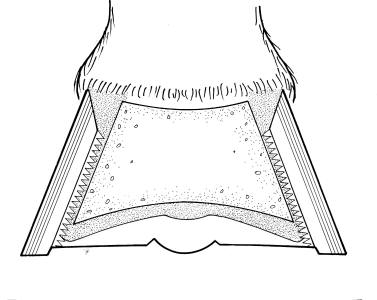

These drawings of the hoof, sectioned crossways just behind the apex of the frog

(as if the toe was chopped off and you were looking at it from the front). Shown

are the coffin bone, surrounding live corium, hoof wall and protective sole and

frog material. Notice in the left photo, the collateral groove would be very

close to the ground because the sole adjacent to the hoof wall is very thin. In

the right photo, the sole is thicker, lifting the collateral groove higher off

the ground. Drawings by Karen Sullivan, reprinted from the book Care and

Rehabilitation of the Equine Foot, P. Ramey.

Once you can visualize sole thickness using the collateral

grooves, the next step will make you more accurate and somewhat able to predict

bone remodeling and/or thin areas of the sole. The horse’s sole

tends to callus into a fairly uniform thickness covering the live tissue

in seen figure 1. Therefore, the sole you see when you pick up the horse’s foot

should be concaved into a bowl-shape with no flattened areas adjacent to the

white line. If you find that a horse’s sole is flat (instead of concaved)

immediately adjacent to the white line, you have either 1) a thinner area of

sole in the flattened region, or 2) a remodeled coffin bone in that region.

Generally, a radiograph is required to tell the difference between the

two, but either way, the area should probably not be thinned more than it

already is.

When these two methods (collateral groove height and

reading the shape of the sole) are combined, they give a quite accurate

estimation of sole thickness all over the bottom of the foot—you can see for

yourself if someone is over-thinning your horse’s sole or trimming areas of the

foot that are already too short. Learning to read the sole will also help you

keep your horses out of trouble by allowing you to notice if they excessively

wear a foot or develop a reduced capacity for sole growth. Protect these feet

with less-abrasive terrain and/or some protective device

before their sensitive tissues are

damaged.