Reversing Distal Descent of P3

(1-12-05) Pete RameyIn the healthiest of equine feet, the

hoof walls should be firmly attached to the coffin bones and the coronet should

lie at the same level or even slightly below the coffin bone (P3). This allows

proper uninhibited motion of the coffin joint. It also ensures the horse can

have a naturally short hoof capsule, while at the same time have thick callused

sole to protect the inner structures. All too often, in our domestic horses, we

see the coffin bones, literally the whole horse, descending through the hoof

capsule over time. Previously, farriers have been left with a very hard choice

with no correct answer. Do you thin the sole to provide the safe and proper

bio-mechanics of a short toe, or leave the foot long, favoring the soundness and

protection provided by adequate sole thickness. Neither bodes well for the

horse. Fortunately, we are learning to truly reverse the situation.

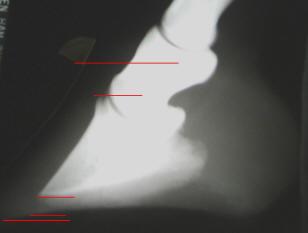

Fig. 1) 18tear old, domestic cadaver

with healthy hoof wall/P3 relationship (sound at death, died in accident).

It has adequate sole thickness and a very short hoof capsule. This healthy

combination is possible, because of the proper relationship between P3 and

the coronet.

Fig. 2) Feral cadaver with healthy

hoof wall/P3 relationship. The lateral cartilages, the laminae and coronary

papillae have been left intact in the photo. Again, we see a very short hoof

capsule (3 1/2 inch toe in a #2 sized foot), coupled with tremendous sole

thickness made possible because of the correct bone/wall relationship.

Fig. 3) Cadaver with severe distal displacement. In this particular cadaver the top of the coronet is actually level with the center of the second phalanx. With this pathological bone position (I should say hoof capsule position, as the bones are exactly where they should be. It is the entire hoof capsule that is truly displaced), it is impossible for the horse to enjoy a naturally short hoof and a thick sole at the same time.

Added 2010: This measurement is now in common use as the CE (coronet to extensor process) measurement.

Important note added in '08:

Notice how steep the coronary groove/proximal end of the hoof wall are. Also

notice that the inner proximal corner of the hoof wall is in the exact

perfect position it should be at the base of the extensor process. In

digital lateral radiographs we can clearly see this shape of the proximal

end of the hoof wall and its position on P3. Typically a case like this is

quick and easy to reverse. The proximal end of the hoof wall simply relaxes

to a lower angle; the laminae and coronary papillae do not actually have to move. However, if you

see the inner corner of the proximal end of the hoof wall (at the

lamellar/coronary junction) is displaced from the base of the extensor

process, the case will tend to be far more difficult to

rehabilitate/reverse. Do-able, but never 'smooth'.

How does this

happen to begin with? Most professionals consider it to be

an immediate and irreversible result of chronic laminitis.

The laminae lose all integrity and P3 drops to the ground

through the hoof capsule (the classic sinker). While this

does occasionally happen, it is more commonly a very slow

process over the course of several years. It is truly an

epidemic in sport horses, particularly among jumpers.

Dr. Bowker and his team of researchers

at MSU have confirmed what many insightful farriers

suspected all along. The horse was

never intended to

hang from the laminae. The hoof walls, soles, bars and frogs

are supposed to work in unison to support the horse.

Trimming and shoeing practices that force the hoof walls to

bear all of the force of impact create more constant stress

than the laminae were ever intended to withstand. Add to

this the constant stress of landing from jumps, or toe first

landings throughout life caused by weak, underdeveloped

frogs and digital cushions -- The result is a gradual downward

movement of P3 (relative to the coronet) over time. This is

remarkably common, but seldom recognized until the horse

finally becomes lame.

That's why so many horse's hooves seem

to get longer as they age. Our predecessors knew this at

some level. It's hard to find an old shoeing text that

doesn't recommend barefoot periods in the "off-season" to

"drive up the quick." What they were actually doing was

driving up P3, relative to the coronet. As we have shifted

away from this old standard and back to back shoeing has

become increasingly common, it has gotten very difficult to

find mature horses that do not have much of the pastern

buried within the hoof capsule.

Once you learn to look for it, you will

spot it to varying degrees everywhere. The most accurate

way, of course, is by taking lateral radiographs with

markers that stop at the base of the hair follicles at the

coronet at the center of the toe. In a lateral radiograph,

the hairline should be level with or even distal to the top

of P3 (extensor process). You can, however, learn to readily

spot distal descent of P3 in the field with the trained eye.

The collateral grooves along the frog,

are very consistent in their distance to the sole's corium

(unless subsolar abscessing is present under the collateral

groove). This makes them an extremely reliable landmark for

determining sole thickness (or the distance P3 is off the

ground). If you visualize the natural vault of the sole's

corium and you understand that the bottom of the collateral

groove is consistently about 7/16” inch away from the

corium, you can get a clear estimate of how deep the sole is

covering the rest of its corium.

Basically, you look for the height the collateral groove is being lifted off the ground (or the plane of the shoe) by the outer band of sole adjacent to the white line. In a horse with a 1/16th inch thick sole at the outer periphery, the collateral groove at the apex of the frog will be lifted off the ground very little or none at all. When the same horse builds adequate (1/2- to 3/4-inch) sole thickness under the outer periphery of P3, the collateral grooves will be lifted 1/2-inch to 3/4-inch off the ground by the outer band of sole. They will be the bottom of the "bowl" of natural solar concavity.

Fig. 4) Partially dissected feral cadaver with sole and frog corium, P3 and lateral cartilages left intact.

Fig.4a Fig. 4b

Fig. 4c

Fig.4a Fig. 4b

Fig. 4c

Fig 4a represents a hoof capsule with

the collateral grooves lifted too high off the ground by

excess sole and wall. The hoof should probably be trimmed to

the dashed line to shorten the hoof capsule and allow proper

function and callusing of the sole and frog. Fig. 4b

demonstrates the valuable information we can get in the

field from a shallow collateral groove. If you have done

hoof dissections and understand the relatively consistent

shape of the inner structures, and the consistent distance

from the collateral grooves to the inner structures, you can

very accurately estimate the amount of sole under P3 and the

lateral cartilages. When faced with this "flat foot" many

professionals still try to cut the foot shorter from the

bottom (right side of Fig. 4c). This undermining of P3

leaves the entire horse free to migrate downward through the

hoof capsule.

The left side of Fig. 4c represents the

true need in this situation. We need to build a natural sole

depth to achieve solar concavity and a healthy foot.

Contrary to the way the sketch must be drawn, this generally

does not cause the hoof capsule to become longer. Instead,

the building of the callus drives P3 upward, relative to the

coronet, often shortening the overall length of the hoof

capsule as the relationship between the coronet and P3

becomes more correct.

So in the field, if you see a "long"

hoof capsule with shallow (or normal) collateral groove

depths at the apex of the frog, you can almost count on

distal descent of P3, and should get radiographs and take

corrective measures immediately.

You can also use these landmarks to

ensure your trimming isn't the cause of sensitivity and

descent of P3. The farriers rasp should not get closer

than 5/8 inch from the bottom of the collateral grooves for

any reason. Doing so overexposes P3 and the sole's

sensitive corium and should be considered surgery, in my

humble opinion. [Please read the article,

Understanding

the

Soles at

www.hoofrehab.com

for further clarification

of using the collateral grooves to read sole depth.]

The hoof in Fig. 5 is a classic

example. This was the condition of the front left hoof the

first time I saw it, after four years of lameness through

numerous corrective shoeing protocols. The collateral groove

at the apex of the frog is only 1/8th inch deep. This should

immediately tell you that you will not be able to shorten

this long toe from the bottom. In order to build adequate

sole depth under P3, thus lifting the collateral grooves off

the ground, almost a half inch of sole needs to be built up!

In fact you can clearly see the imprint of P3 on the sole. I

traced its "footprint" with my hoof pick so it shows up

white in the photo. It also should be clear that the walls

are no longer attached to P3 either, and lamellar wedge

(keratin proliferation by the laminae between the dermal and

epidermal laminae) has filled in the void between P3 and the

wall. The material behind the white scratching is sole,

produced from and attached to the solar surface of P3. The

material between the white scratching and the wall is

lamellar wedge.

The bone position is so low in the hoof

capsule – cutting this long hoof to a "natural length" would

actually cause you to rasp away part of P3!

Fig. 5) Front Left foot before setup trim and Fig. 6) same foot eight months later, before six week maintenance trim. P3 has moved upward, relative to the coronet; shortening the hoof capsule while thickening the sole. She had been happily giving lessons for a living for six months.

For an enlightening internal view of this concept, read http://www.hoofrehab.com/Coronet.html.

Fig. 6 shows the same hoof eight months

later, before her six-week maintenance trim. Note that the

hoof has now reached a more natural length, but the

collateral groove at the apex of the frog is now recessed

within a 5/8-inch deep bowl of solar concavity. This

healthier toe length that would have quicked the horse eight

months ago exists with much more armor underneath than it

had then, at the

same time. P3 has moved upward (relative to the coronet)

significantly. At no time was the sole of this horse cut.

This concavity was built, by adding adequate sole thickness

under P3.

The same

horse's radiographs give the same

information. Fig. 7 and 9 were taken a year before I first

saw the horse and the photo above was taken. It appears the

sole was a bit thicker, rotation less and distal descent

less severe at that time, than what I had to start with a

year later. So how do you fix such a situation? The horse

has to be barefoot for a while. The horse got this way by

having its walls overloaded, without the assisting support

through the sole. To reverse it, simply do the opposite. The

first priority is to build adequate sole depth and heavy

callus under P3. Pressure and release stimulates growth, so

the fastest way to do this is to maximize movement while the

hooves are bare or on foam rubber boot insoles.

Fig. 7) [Left photo- Front Right Before] and Fig. 8) [Right photo- Front Right (same foot) 3 years later]

Fig. 9) [Left photo- Front Left Before] and Fig. 10) [Right Photo- Fr. Left (same foot) 3 years later]

At the same time, the walls should be

rolled or beveled out of a "lifting role" and P3 should be

loaded through the sole so the coronet can migrate toward a

more natural position relative to P3. One might think that

if we add a half inch of sole to a hoof this long, the hoof

capsule will end up even longer. The opposite is true. With

the walls rolled and the sole unmolested and callusing, the

hoof capsule actually becomes much shorter as the coronet

moves down to its normal position relative to P3 and the

lateral cartilages.

I need to stress to use hoof boots with

padded insoles if there is any discomfort, if the soles are

thin, or if the terrain is rocky. Running around in rocks on

a thinned sole is dangerous. You need to build a thick

callused sole before you do that. Pressure to an

unnaturally thinned sole can cause bruising and can even

restrict blood supply to the sole by restricting flow

through and from the circumflex artery that follows the

perimeter of the distal border of P3. This can "starve" the

sole and reduce the sole's ability to thicken and callus.

Keep the horse on yielding terrain at first, and/or use the

foam insoles in boots to avoid this pitfall.

It is

critical that any means of sole support provide a total

release of pressure to the solar corium during hoof flight-

This is why I prefer boots over fixed shoeing systems for

laminitic horses (and for horses that aren't laminitic yet).

I usually use dense foam rubber insoles (1/2 inch thick). Many combinations will work, but over the counter, I've had the best results with Easyboot Epic Boots, and their Comfort Pads available as accessories. Read the article http://www.hoofrehab.com/BootArticle.htm for more specific information.

In this particular case, however, the horse became comfortable immediately when the pressure was relieved from the disconnected walls and lamellar wedge; there were no rocks in the environment, so the horse was worked and turned out bare. Let the horse be the judge and use the pads and boots for any situation that causes discomfort or possible bruising.

The Quarter Horse hoof in Fig. 11 shows

the basic trim we use to help move P3s higher in the hoof

capsule. It is also the very fastest way to grow out white

line separation or hoof capsule rotation I've ever seen, so

it makes a great tool for any farrier's bag of tricks. It's

tempting, I know, to want to cut that sole down below the

wall at the toe, making it "passive." You have to realize it

still won't be passive in varied terrain, but the sensitive

structures will just be closer to the outdoors. Let the

callus build (unless the collateral groove depth at the apex

of the frog exceeds

3/4-inch). This horse only has 1/4-inch of collateral groove

depth. We still need to build more sole under P3 to drive P3

upward as the coronet relaxes into a healthy position.

In the real world, when the walls are trimmed this way, they aren't quite as passive as it may appear. As the hooves sink into terrain and of course after breakover as the horse is pushing off its toes, the walls are definitely still doing a share of the work. The bevel causes the force to be directed inward a bit, so stress on the laminae is minimal. In fact, I estimate that in yielding terrain or rocky terrain, there is more of a "squeezing together" force on the laminae than vertical sheer force. This becomes even more important if a bad diet is weakening the laminae. Read http://www.hoofrehab.com/Diet.html.

Don't bring the large bevel onto the

heel buttress. In fact I usually only bevel from the widest

part of the foot forward. The heel buttress must be left

strong and intact in every circumstance. Like the sole,

allow frog to build into dense callus. Routine frog thinning

can cause sensitivity and a toe first landing. It is very

important that you achieve heel-first impact with these

horses (at any gait faster than the walk; a flat impact is

okay at the walk). Toe-first impact will continue to drive

P3 lower into the hoof capsule no matter how you trim or

shoe.

Fig. 11) Trimming to move P3 upward in the hoof capsule and grow out white line separation or capsule rotation. Repeat at 4 week intervals, never allowing the walls to lift the sole out of a support role. Use yielding terrain free of rocks and/or boots with padded insoles to protect the solar corium during the process.

Why is it difficult or impossible to

lift P3 higher in the hoof capsule with fixed shoeing

methods? There are two important reasons. First, according

to Bowker's research the sole "hates" constant pressure, but

"loves" and grows the best with continued pressure and

release. Second and most important, the hoof wall grows much

faster than the sole or frog. If you attach perfect P3

support to the hoof walls today, by tomorrow your support

has crept away a tiny bit. Four weeks later, the support may

have moved distally 1/4-inch or more and in an already

compromised situation, P3 is free to migrate right on down

with the "fixed support" and the growing walls. Am I

suggesting that farriers start carrying around a stock of

hoof boots and rubber insoles? If they work with foundered

horses or work to keep sport horses at optimum performance,

yes. They can reap tremendous results during the "off

season."

Fig. 12 shows the front foot of a

teenage feral cadaver that died on the range in a cattle

grate. This healthy vertical relationship between P3 and the

hoof walls exists in our foals, and should remain there

throughout life. If you monitor and maintain this

relationship in the horses in your care you will help ensure

healthy hoof function and joint mobility. It will also allow

them to enjoy thick callused soles and naturally short

breakover - all in the same foot. The reversal of distal

descent is a slow process. The most important thing to

understand is it is much easier to prevent. Keep foals

trimmed, never allowing the walls to lift the sole out of an

assisting support role. Avoid carbohydrate overload and

mineral imbalance, which can constantly weaken the laminae.

Give shod horses a barefoot period in the off-season while

continuing a strict, routine trim schedule. A little

prevention can add years to the horse's life.

Once an adequately thick layer of callused sole covers P3, the resulting shape of the sole mirrors the inner structures and the collateral grooves will be lifted 5/8"- 3/4" off the ground, even with a very short overall hoof capsule length. At this point, start leaving the walls 1/8"-1/4" longer than the sole plane while continuing to rasp the same straight bevel on the outer wall. The result is incredible traction, performance and hoof function.

Fig. 12) Teenage Feral cadaver. This adult horse kept the P3/wall relationship of a newborn foal throughout life - without man's "help." Let's make sure we provide hoof care that is better than none at all.

For a deeper understanding, read the companion article http://www.hoofrehab.com/Coronet.html.