Toe and Heel Length

(11-25-06)

Pete Ramey

Copyright 2006

This article was written to provide additional clarity to the previous article, Reversing Distal Descent http://www.hoofrehab.com/DistalDescent.htm. Please read it first.

If you've read my work before, you

know how much I stay away from "always and never"— the horses

taught me that. In this article you'll read those words

repeatedly. Please know I do not use them lightly.

Most hoof care professionals were taught to

trim hooves to certain parameters based on toe length and heel

height. The target ranges vary from method to method, but most

call for toe lengths from 3 to 3-1/2 inches and heel lengths

from near zero to 2 or more inches. The problem with trimming

theories that enforce specific hoof lengths based on

measurements from the coronet to the ground is that they don't

take into account the fact the coronet is highly dynamic and

easily moveable. Excess pressure on the walls can quite easily

displace the coronet upward. It is the last place we should

measure from! I'm going to try to spin your brain into

seeing past the coronet and the hoof wall; everyone who cares

for horses' hooves needs to see the internal structures first.

The hoof wall was never intended to bear

the horse's weight alone. The sole, frog and bars are supposed

to work in unison with the hoof walls to support the impact

energy of the horse. It is common, however, for traditional

farriers to force the hoof walls to unnaturally bear the entire

burden of support. Over time, these unnatural loads on the walls

push the coronet to a higher position (relative to the coffin

bone). To put it another way, the entire horse drops through the

hoof capsule. Traditionally, this is thought of only as an event

associated with severe founder, but it is actually very common

to varying degrees in domestic hooves that are perceived as

perfectly sound. They often get along this way for years before

it catches up to them and causes severe lameness (actually, the

lameness is typically caused when the farrier doesn’t realize

the horse has sunk through the hoof capsule and then cuts the

sole off in the name of shortening the foot).

At the toe, this type of damage is readily

visible on radiograph if a radiopaque marker is accurately

placed at the hairline (Please see the previous article

Reversing Distal Descent). The coronet height and the coffin

bone height should be very close to level with each other.

2011 Edit: since writing this article, the term CE –

coronet to extensor process (the top of the coffin bone)

measurement has come into common usage. This is measured from a

scaled lateral radiograph by marking the exact base of the hair

follicles at the center of the toe and comparing this height to

the height of the top of the extensor process.

The foundation for the back of the foot is

cartilage rather than bone, so it doesn't show up on radiograph,

making it more difficult to interpret. When people debate

proper heel height or toe length without considering where

the highly mobile coronet currently resides they are missing a

critically important point. It is very common for soles

to be thinned to dangerous levels in an attempt to achieve

certain toe lengths. It is equally common for the sole in the

back of the foot to be dangerously thinned to achieve certain

heel heights as well.

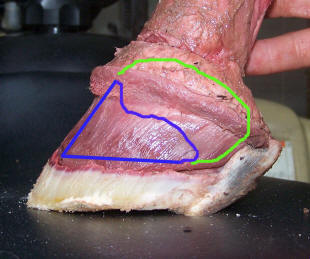

Every hoof practitioner

should do as many cadaver dissections as possible. This is the best way to

develop an understanding of the internal structures. Here I have removed the

'skin' -- which is precisely what the hoof wall, sole and frog are.

Left

photo: (please excuse my lack of talent with graphics) Blue line

represents the coffin bone; green line represents the lateral cartilages.

Both "foundations" are covered by a thin (3/16th inch) layer of living

tissue (the corium). It is very important to understand the shape of the

internal structures. A horse must always have at least 1/2-inch of

densely-callused sole and frog covering them – 3/4-inch is even better).

Every situation

is different, but every horse needs adequately thick and

densely callused sole under the coffin bone and the lateral

cartilages. This should be priority #1 in all circumstances.

Once that is achieved, if the heel or toe wall length is "too

long" the coronet has been pushed into an unnaturally high

position by excess wall pressure over time. Providing proper

movement, diet and trimming will allow the coronet to relax to a

natural position over time, thus shortening the wall length. The

flip-side of this is that if you thin the soles to achieve

'correct' wall lengths first, the horse will work overtime to

replace the lost armor plating and the 'extra' length you

removed will keep coming back indefinitely, often getting worse.

How do you apply this? First, forget about

the length of the hoof walls (toe, heel, quarters...

everywhere). The top priority is to ensure there is adequate

(but not excessive) sole under the coffin bone and lateral

cartilages. There are at least two accurate ways to judge sole

depth in the field. First and foremost is sole callusing.

Barefoot horses that move correctly tend to callus their own

soles very uniformly and in a 1/2- to 5/8-inch thickness and

this callus shouldn't be molested with the tools. Look for this

callused sole plane and you'll find it is almost always parallel

to the internal structures. Exceptions occur when the horse has

had its soles thinned by the previous trimmer, or when the horse

is moving incorrectly. A common example is the horse that lands

toe-first due to heel pain. The soles at the toe will almost

always be worn thinner and the coffin bone will almost always be

driven to a very low position in the hoof capsule. Horses with

angular limb deformities may also wear the sole on one side to a

thinner depth, but this is very rare. It can go the other way as

well: Shod horses and sedentary barefoot horses (particularly in

arid regions) may have false soles or layers of old growth that

should generally be removed.

For sorting through these exceptions, plan

B is to judge sole depth using the collateral grooves (frog/sole

junction). Their deepest point along the sides of the entire

frog is consistently around 7/16th inch away from the corium

covering the coffin bone and lateral cartilages so they provide

an excellent locator. The more sole depth there is in the

outer perimeter adjacent to the white line, the higher the

collateral grooves will be lifted off the ground (plus any wall

height standing longer than the sole). In a healthy hoof with

adequate sole depth, the sole adjacent to the white line should

lift the collateral grooves about 3/4-inch off the ground in

front, and around an inch off the ground at the back of the foot

at the deepest point beside the bars (This extra height at the

back of the foot allows for expansion and a ground parallel

collateral groove at peak impact loads).

The collateral groove is a very accurate

evaluation for sole thickness in the front of the foot, because

the coffin bone is [more] rigid, but the flexion of the lateral

cartilages makes it trickier to gauge in the back of the foot.

For instance, in a hoof with contracted heels the lateral

cartilages will be 'bent' up into a higher dome. This may mean

1-1/2 inches of collateral groove height is necessary to provide

adequate sole thickness adjacent to the white line. Therefore

the callused sole plane is the best guide in the back of the

foot and the collateral groove depth adds additional

information. The collateral groove depth is the most accurate

guide in the front of the foot, with the callused sole plane

providing the back-up information (Please read the previous

articles, Understanding the Soles and

One Foot for all

Seasons for clarity).

So by using this information to judge sole depth covering the internal structures, you can then determine whether the coronet is displaced to an unnaturally high position. If the coronet is in a correct position and adequate sole thickness is present, toe lengths (based on measurements to the hairline) should then fall between 3 and 3-1/2 inches and heel heights should be around one inch in most horses; the shorter the better, really. If the wall lengths are longer, either the coronet is vertically displaced, the toes are flared from the coffin bone, and/or the heels are contracted (raising the vault of the lateral cartilages). In none of these cases is it even remotely correct to thin the sole to achieve proper wall lengths. That would just add insult to injury. The wall length (at heel or toe) should be the very last thing we judge or act upon, but so often people attack it first at the expense of the sole. Why? There are hundreds of different books that teach us to do so!

When you realize how dynamic the coronet actually is, it becomes sobering to think how many rash decisions are traditionally made from the measure of hoof wall length. Here, I am moving the coronet almost an inch with light thumb pressure.

The same

information and insight into the internal foundation will help

you with the toughest medial/lateral balance problems. First

understand no one can balance a foot. It simply isn't possible.

If you show me a 'perfectly' balanced foot, I'll lead the horse

through a turn and we'll watch the heels collide with the ground

out of unison. So what is proper heel balance? Proper heel

balance is having the exact same amount of sole covering the

lateral cartilages on both sides of the foot, and the same

amount of hoof wall on each side protruding above that sole

plane. (Please read the previous articles

Heel Height, the

Deciding Factor and Mediolateral Balance

for clarity

and exceptions)

The horse needs for both heels to impact

the ground simultaneously as often as possible, but varying

terrain, the type of movement/work the horse does and the

straightness of the limbs makes every impact a little different

in the real world. The natural flexion (twisting) of the lateral

cartilages conforms to the ground and easily accommodates this,

but for additional help they also do an amazing thing. The

lateral cartilages semi-permanently adjust their rest

position to accommodate the most common impact of an individual

hoof. A hoof that usually hits the ground slightly crooked

because of an angular deformity or body issue will adjust its

lateral cartilages accordingly. Also, a perfectly

straight-legged horse can make such adjustments due to its most

common work. For instance at the trot, a horse should impact the

ground with its hind limbs underneath himself (like a

tightrope walker). Horses that usually work at the trot

(endurance horses, trotters...) will develop lateral cartilages

that are in a lower position on the inside (or from the

trimmer's perspective; the hoof will appear longer on the

inside) so that both heels hit the ground simultaneously during

this movement. This is a good thing and should be allowed and

embraced by the trimmer (but do not let it run away out

of control).

If the trimmer/farrier doesn't consider the

movement of the horse and tries to fight this adaptation by

forcing the foot to be balanced while standing square, the

resulting "excess wall" (from the horse's perspective) will

cause the coronet to push upward over time. Again this is very

common and again the hairline or coronet balance should be the

last thing we evaluate; it is only a view of the past care. I

have seen many horses with horrifically displaced/imbalanced

coronets, but have never seen a situation that required one

lateral cartilage to be covered with more sole than on the other

side of the same foot.

Therefore, we're right back to the same

spot when trying to sort through heel balance issues: Use the

callused sole plane and collateral groove depths to ensure you

have the same amount of sole on each side and do nothing more

than monitor the hairline height off the ground at the heels.

The hairline/ground height will equalize over time if the horse

is allowed to wear the heel balance that agrees with its

movement and the position of the lateral cartilages. [This

can/should be accelerated by putting a more aggressive (steeper)

mustang roll/bevel on the side that has the high coronet].

Every horse and every hoof is different. I

still run into new situations that leave me "head-scratching"

every day, so there is no way to sit down and write about each

possible situation you'll encounter in the real world. I can

tell you that the more you learn to "see through" the hoof wall

and visualize the internal structures, the better you will be at

sorting through every hoof issue. The best help for this is by

performing as many hoof dissections as possible. Never bury a

hoof; you'll be missing out on a chance to make yourself better

for the horses in your care.

Besides CE, there are countless other factors make the correct toe

length and heel height a variable. Sensitive and underdeveloped lateral

cartilages and digital cushions may cause a need for a higher heel, as may

ligament, tendon, joint and muscular issues. Flared or rotated toe walls can

dramatically effect toe length measurements. The list goes on and on.

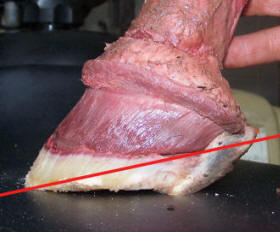

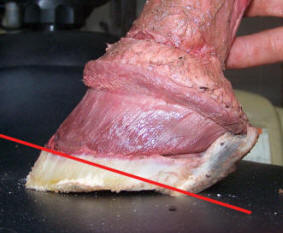

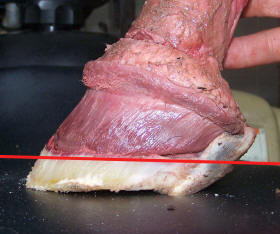

But with all the "ifs, ands and buts" we

have to sort through every day, at least one thing is consistent. It is

simply never desirable to thin the soles beyond their 5/8”-3/4” natural

thickness. The left photo shows the naturally thick and uniform sole of a

healthy horse. The other three (red lines) show very common mistakes I see

every day. How is it even possible for a professional to do this? A vast

majority of professionals were trained to place top priority in heel and toe

wall lengths/angles, sacrificing the sole thickness. Many barefoot trimmers

will cut into or near the corium trying to shorten heel walls and bars. Many

farriers will routinely take much needed sole from the toe, trying to

shorten the toe walls or raise toe angles. I hope this article makes this a

little less common.

Burn these pictures into your

brain and every time you see the sole being trimmed, always ask yourself

which of the four pictures is most similar to the end result.