Breakover 2-15-05 Pete Ramey with 2018 edits

Note: If you are

new to hooves and the terminology used here, as a prerequisite,

read the 12-article series

http://www.hoofrehab.com/HorsebackMagazineArticles..html

. Written for lay horse owners, they provide a good introduction

to hoof care and rehab.

The breakover point

on the horse’s foot is the area at the toe that the horse pivots

on and pushes from as the heels leave the ground. It is not

necessarily the farthest-forward part of the foot – think of the

ball of your own foot, which bears the brunt of pushing into the

next stride, vs. your toes, which are actually farther forward,

but doing little-to-no work as you pivot, leap or run.

As with your own

foot, the horse’s natural breakover point is comprised of

hard-callused sole, backed up by bone. This does not mean the

horse’s hoof wall does not do hard work – but the wall is

typically worn or trimmed/rolled back from the breakover point

so that it does not become engaged until a little later in the

stride after initial breakover of the foot.

Many people think of

breakover as occurring only at the center of the toe, but

actually it can occur anywhere around the foot as the horse

turns or navigates uneven terrain. Therefore, the shape of the

breakover point on the horse is round – a projection of the

shape of the coffin bone (P3).

The sole at the

outer periphery of P3 should be allowed to callus into dense

material 5/8”to 3/4" (15-18mm)-thick to accommodate the

incredible forces that occur to the region. Special care must be

taken by the farrier or trimmer not to rob the horses of this

necessary armor during maintenance trims (a true epidemic in the

farrier world), and if a horse has 1/2" (12mm) or less sole

thickness covering the outer periphery of P3, then hoof

protection (my personal favorites are hoof boots with padded

insoles) must be provided when riding, particularly on firm

terrain.

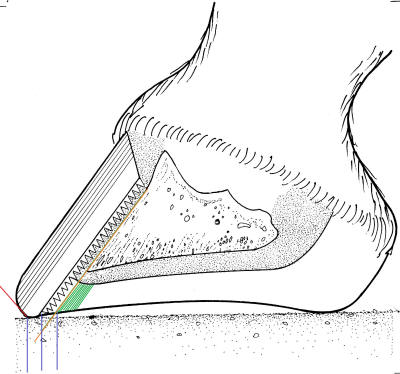

Figure 1

In a healthy hoof

with perfect lamellar connection [Figure 1] setting the correct

breakover point is easy. If you were to project the line of the

dorsal aspect of P3 to the ground (orange line) around the

perimeter of P3, you are simply outlining the sole. In front

feet, measuring from the sole, allow for 1/8” (3mm) of white

line width (the white line – never white in color – is made of

50% epidermal laminae, 50% sole. Thus it is the bond between the

hoof wall and the sole in healthy situations). Allow another

1/8” (3mm) of hoof wall to bear active ground pressure (blue

lines) around the outer perimeter, then roll the wall on a 45-60

degree angle (red line). In other words, with tight lamellar

connection, you simply roll/bevel the walls to achieve natural

breakover for the horse. The densely callused sole around the

outer periphery of P3 (green shading) will still bear the brunt

of the ground force at the toe in most terrain, even though in

these healthy, well-connected feet the wall is technically

sticking out a bit longer and more forward of this rim of

callused sole backed up by the cushioned design of the solar

corium and by bone.

On hind feet with

adequate sole thickness, I generally place breakover all the way

back to, or only 1/8” (3mm) outside the perimeter of this true

sole supported by P3.

This healthy,

natural breakover point allows the horse to move correctly. The

foot can stay on the ground longer (than if the breakover were

farther forward), thus fly lower, farther in a long, efficient

arc. The resulting long stride allows time and extension for the

horse to load the heels at impact, taking premium advantage of

the energy dissipating features built into the foot and each

limb.

Finding and applying

this correct breakover point gets much more complicated, though,

when the hoof walls have become flared or rotated away from the

bone [Figure 2]. The limbs, muscles, ligaments and tendons still

have the same breakover needs for optimal movement and

efficiency. When the toe wall migrates forward of its normal

position around P3, it creates a biomechanical nightmare for the

horse.

The typical result

is that the horse has to step (breakover) a little earlier in

the stride, lifting the foot more steeply to allow time to step

over the longer toe (think of yourself walking in swim fins) and

to avoid the pain involved in this now-increased stress and

lever forces on the laminae. This generally alters the whole

stride into a higher, shorter arc causing the foot to land

toe-first because there is not enough stride extension for the

horse to load the heels. Toe-first impact is one of the primary

causes of toe flare and hoof capsule rotation – so a viscous

cycle is created. The flip side of this is that the number one

trick to growing out wall flare and hoof capsule rotation is

achieving flat impacts at the walk and heel-first impacts at

faster gaits. This means you will have to optimize breakover on

these horses to eventually grow in well-connected walls.

Alternately, as the

pain of separating laminae becomes more severe, the horse might

start to avoid breakover completely, keeping the feet out front

at all times, exaggerating the heel load. This is a defense

mechanism that takes stress off the separating toe wall and thus

the laminae. Again, in this case, the same trim relieves lever

forces on the toe wall, usually eliminating the need for the

horse to stretch back in this “founder stance” or move in this

pattern. This is also helpful for growing in well-connected new

laminae.

Figure 2

The lamellar wedge –

the area between the now separated hoof wall and P3 varies

dramatically in its texture and integrity. Sometimes it is an

air space or bacteria-infested mush, sometimes it is made of

harder material than the sole, sometimes it is anywhere

in-between those extremes. Occasionally, all or part of the

lamellar wedge is covered over by old sole material which has

been distorted forward of proper support by P3. But the callused

outer periphery of the sole – the tough “extension” of P3 (green

shading) is generally still in the same spot relative to P3.

Using radiographs, or often you can simply see the difference

between the textures and colors of the true sole and the

lamellar wedge, try to locate the border between the true sole

and the lamellar wedge material. If you can find it,

biomechanically, this should be the breakover point, with the

roll beginning 1/4" outside that perimeter (blue lines) to

protect the corium. Assuming the sole is of adequate thickness

(over 1/2"- or 12mm-thick), the wall and lamellar wedge should

be trimmed from this point with the nipper or rasp held on the

angle of a normally rolled wall (red line in Figure 2).

BUT… If the sole is

thin, I cheat the breakover forward by 1/2”-5/8” (12-15mm)

simply to leave extra padding out front. Optimizing breakover on

a thin-soled horse often leads to overexposure of the dermis,

then bruising, then abscessing and P3 remodeling… not worth the

potential gain. If an appliance is being added, whether a boot

or shoe, then go ahead and optimize breakover on that appliance

– but don’t do so on the foot until the sole is 5/8”

(15mm)-thick or more.

The reasons behind

optimizing breakover in a case like this are, 1) improve overall

stride to get the horse loading flat/heel-first so that

well-connected walls/laminae can be grown, and 2) to relieve the

lever forces prying away at the lamellar connection so that

well-connected walls/laminae can be grown. If you manage to get

the breakover back far enough to achieve those two goals, it is

back far enough – no need to increase risk to the corium by

bringing it back farther when the soles are thin.

Trim more often,

rather than taking the risks associated with over-trimming. Trim

just enough to keep the new growth at the coronet from levering

away from the bone during the next 3-4 weeks. Then come back 3-4

weeks later and do it again. If, instead, you trim so much wall

that lever forces will be relieved for 8 or more weeks, the

likelihood of increased pain and corium damage increases.

Figure 3

Eventually, this is

the goal: [Figure 3] to grow in a normal wall/lamellar

connection around the existing P3 (dashed line). There will, of

course, need to be very careful heel work done and probably

sweeping nutritional changes needed to achieve this, but keeping

the breakover trimmed correctly along the way is a big part of

success with these cases.

See the articles

http://www.hoofrehab.com/HeelHeight.html

and

http://www.hoofrehab.com/Diet.html

Important note: In a

rotated or severely flared hoof, do not trim the dorsal wall to

the dotted line in Figure 3 – wait for the new well-connected

growth. Instead, top dress the dorsal wall similar to the purple

line in Figure 2. In order for the generally weaker lamellar

wedge material to protect the dermis as well as a healthy hoof

wall would, it needs to be about twice the thickness of normal

hoof wall. Trimming the lamellar wedge down to normal wall

thickness (1/2”-5/8” or 12-15mm) overexposes the dermis to

damage.

Figures 4 and 5

On rotated, flared or exceptionally low angled hooves, any boots or shoes applied should have the breakover modified to optimize movement and efficiency. With hoof boots, in some cases this can be achieved by rasping a more aggressive breakover into the boot tread. In more severe cases, heat-fitting and/or toe-slotting Easyboot Gloves may be required. See http://hoofrehab.com/GloveMod.html

Looking for texture

and color differences on the bottom of the foot is often

effective for locating the true sole supported by P3. Careful

though, some soles have striped pigmentation. Don’t make

breakover decisions based on color alone – look for the texture

and prominence as well. Some lamellar wedges are tougher than

the sole and will be protruding past it. Other lamellar wedges

are softer than the sole and will have worn off passive to the

sole. Use lateral radiographs, as well, to help you determine

where each tissue grew from. If you draw a line down the dorsal

aspect of P3, generally the tissue behind the line is true sole

and the tissue between the line and the wall is lamellar wedge

material.

Figures 6 and 7

Figures 8 and 9

In Figures 6, 7 and

8, it is easy to see the boundary between the true sole and the

lamellar wedge (yellow line). If the sole is over 1/2”

(12mm)-thick, breakover should be brought back to 1/4" (6mm) in

front of the true sole, well into the lamellar wedge material

(Figure 9). Warning: this horse will need 24/7 boots with padded

insoles and/or soft terrain until well-connected wall has been

grown.

Figures 10 and 11

Five months later

(Figure10 and 11), the walls have grown in much

better-connected. Now getting breakover right only involves

rolling the wall – the lamellar wedge is almost gone.

Figures 12 and 13

Combining

Radiographs and Visual Indicators to find the True Sole,

Supported by P3

The foot in Figures

12 and 13 has an obvious line between the true sole (outlined by

orange dots in photo) and the lamellar wedge (black, weak,

infected). The radiograph confirms the presence of the lamellar

wedge to erase any doubt about the hoof capsule rotation present

here.

By projecting the

dorsal aspect of P3 to the ground (orange line on radiograph,

orange dots in photo), then moving forward 1/2" (6mm) (red

dotted line), the natural breakover around P3 can be created

(red line in radiograph and photo).

Figures 14 and 15

Five months later,

as the well-connected walls and laminae grow in, breakover can

be optimized by simply rolling the wall. The “right” breakover

point has not changed at all throughout treatment, though the

application of it has changed dramatically.

Figure 16

Remember that when the sole is thin it is a

mistake to optimize breakover when trimming the foot. Whether by

projecting the dorsal aspect of P3 to the ground (blue line) or

by seeing the boundary between the true sole and the lamellar

wedge, if you move forward 1/4" (6mm) from the true sole line

and place breakover (yellow line), the corium (red line) will be

overexposed to impact trauma. Instead, cheat the breakover

1/2"-5/8” (12-15mm) farther forward (green line) until the sole

thickens. During this time, of course, be sure no one is

trimming the sole – this is too common.

Alternate Methods

for Finding the Natural Breakover Point

In horses, the apex

(front of) of the frog consistently grows/originates from a

point 1/2" (12mm) or so behind the tip of P3 (not true in

donkeys and some mules). So – to an extent – in horses, the apex

of the frog and overall frog length can be helpful in finding

the natural breakover point when there are no fresh radiographs

and when you cannot see a distinct line between the sole and the

lamellar wedge (which is an indicator of P3 remodeling). Note:

when measuring to the apex of the frog, be sure to measure to

the bottom of the collateral groove (the tight seam between the

frog and sole), ignoring any overhanging flap of frog material.

If you measure the

overall frog length (including the bulbs) in most horses, then

divide that number by three, the resulting measurement is

approximately the distance from the leading edge of the true

sole to the apex of the frog, so very close to where the

breakover should be located. There are exceptions to this:

· Healthy development of the lateral cartilages and digital cushions makes the frog larger/longer in proportion to the size of P3.

·

There is some

individual variance from horse to horse of where on P3 the frog

corium originates.

·

Distal descent of P3

can elongate the frog.

·

Horses with P3

remodeling (bone loss at the outer periphery and/or ski-tipping)

generally have the tissue of the frog apex originating closer to

the forward edge of (or even in front of) P3.

·

Under-run distortion

of the hoof capsule and heel bulbs can artificially elongate the

back of the frog, thus the overall frog length.

Each of these exceptions makes setting

breakover 1/3 of the frog length in front of the frog too

conservative or too far forward. But this means, at least, that

this ratio is a good place to start when you have no

other indicators. Again, when the soles are thin [collateral

groove height less than 1/2" (12mm) off the ground], don’t

optimize the breakover. Instead set breakover at half the

total frog length in front of the apex of the frog as a very

safe starting point.

Figures 17 and 18

Another useful tool

to help find this same breakover point is to project (not cut!)

the upper 1” (25mm) of new wall growth to the ground, then add

the typical 45-60 degree roll to the lower portion, simulating

the dimensions of a normal “mustang roll” on the wall. In

Figures 17 and 18, using the same hooves previously discussed,

if you project the angle of the upper 1” (or more) of new growth

to the ground (blue lines) it will approximate the same

breakover point, unless that upper growth is also rotated. Even

then, it will get you closer than if you simply rolled the

existing rotated wall at ground level.

Don’t use less than

1” of growth for this projection! The coronet can bend, distort,

and thus trick you into being too aggressive if you try to do

this with a shorter length of new hoof growth.

Figure 19

Using all of the

above indicators in unison is considerably more accurate than

using any one of them alone. In the foot in Figure 19, I set

breakover at 1/3 of the frog length in front of the apex of the

frog (blue vs. yellow lines). This helped me notice a very

subtle sole/lamellar wedge line (red dashed line) I might

otherwise have overlooked.

Figure 20

Be willing to go

outside the box, rather than blindly following methodology. The

Thoroughbred above has a thin sole and is getting much of its

vertical depth/height off the ground from a proud rim of

lamellar wedge around the outer periphery. Don’t bring breakover

back so far that you would lose vertical height/depth. Remember

that the reason for optimizing the breakover is correct and

comfortable movement. This trim achieved these for the horse,

while also providing more protection for the corium than it

would have if I had brought breakover back farther.

Figure 21

With bare feet, from

10:00 to 2:00 around the toe, horses seem to care very little

about whether hoof wall is standing longer than the sole. In

this region, if the soles are of healthy thickness, it is

generally safe to bring breakover back so that the walls appear

unloaded when the horse is standing on a hard, flat surface. I

believe this is because horses don’t actually need a toe wall

for standing still on a hard surface – they need a toe wall when

they are propelling themselves along through their home and work

terrain. So a foot with the breakover trimmed as in Figure 21

has a very active hoof wall engaged after breakover when the

foot is tilted up higher and the horse is pushing off the toes.

But from 10:00 to

2:00, back, horses do seem to care more about whether wall is

sticking up past the sole. It is much more likely that you will

make a horse tenderfooted if you don’t leave 1/8”-1/4” (3-6mm)

of wall standing past the sole at the quarters and heels.

There is a time and

place to unload big quarter flares – this is just to say that it

cannot be done nearly as routinely as at the toe.

Important note:

When hooves are bare, booted, have tape-on pads, epoxies and

with some thoughtful glue-on applications, the solar corium

receives huge loads from impact through breakover, and a 100%

release of that load when the foot is in flight – this is the

natural way the sole should be loaded and does not seem to cause

a lot of problems. But beware of shoeing with sole pressure, as

this pressure is “clamped on,” so is not fully released during

hoof flight. The solar corium, like all living tissue is quickly

damaged by constant pressure without release.

Figures 22 and 23

Another variance I

commonly need to do occurs when a foot has wholesale wall flare

all the way around the foot, or at least one big quarter flare

along with a toe flare or hoof capsule rotation. In the foot in

the Figures 22 and 23, if you trimmed aggressively to try to

grow out the rotation, and both quarter flares during the same

visit, the horse would almost certainly be lamed and in danger

of bruising of the corium, particularly if any of the horse’s

terrain was firm or rocky. Even worse, the resulting

compensative movement would probably make growing in

well-connected walls impossible, anyway. So instead of trying to

do it all at once, I find it important to “pick my battles.” In

this case, I felt that toe-first impact and discomfort caused by

the rotated toe wall was causing the primary problems. So from

10:00 to 2:00 around the toe, I optimized the breakover.

At the quarter walls

and heels, I took a more passive approach – I left the walls

standing well past the sole and just rolled/beveled their entire

width. Remember the real secret to growing out wall flare is

flat and/or heel-first impact, anyway.

The result of being

aggressive with the toe wall and more conservative with the

quarter walls is a “squared off” look that I am generally not a

fan of. In this case, though, it is the right thing to do. At

some future trim, when I am not making a big breakover change, I

might “pick another battle” and go more aggressively after one

or both of the wall flares. Eventually, when well-connected

walls/laminae have been grown in everywhere, the foot will be

round – following the shape of P3. But this method is often a

very important means to that end.

Figure 24

In this foot, the border between the true sole and the

lamellar wedge is marked by the blue dashed line – this horse

has about a 10 degree hoof capsule rotation. Everything between

the blue line and the wall (green line) is lamellar wedge

material. This photo shows a variation to trimming I commonly

use when soles are moderately thin – 3/8” (9mm). To leave

adequate protection for the corium while simultaneously

optimizing breakover, I place a slight bevel on the entire width

of the lamellar wedge (10-30 degrees, depending on how close the

solar corium is to the outdoors). Then the wall is rolled

normally. Notice the sole was not touched, but was allowed to

keep all callusing and thickness. This horse is comfortable

barefoot in the turnout environment and ridden in boots with

padded insoles while I grow out the rotation and wall cracks.

The breakover point is back at the supported sole (blue line),

while adequate armor is left out front.

Alterations

Aside from normal or natural breakover discussed here, there is

a long list of issues – really any injury or biomechanical

problem a horse might have – in which altering or exaggerating

the breakover farther back might help the horse move better.

These generally warrant experimentation and careful scrutiny of

the horse’s movement to find the “right spot” for breakover. I

caution you again, though, to do these alterations on the

appliances you use, whether nail-on, glue-on, epoxies,

urethanes, or boots. It is important that you not over-trim the

foot itself in the name of some other issue the horse has. Don’t

trim sole unless, perhaps, it is over 5/8"(15mm)-thick and leave

at least 1/2" (12mm) thickness of good, solid hoof wall or 1”

(25mm) of lamellar wedge out front to simply pad the corium from

impact trauma. And if you find less material than this already

present upon your initial visit, be sure to treat the horse as

compromised – provide protection in some form, and/or make sure

the terrain is soft, until the protective tissue has reached

these adequate thicknesses.

All photos are from

Pete Ramey’s files or from the book

Care and Rehabilitation of the Equine Foot. Black

and white line drawings by Karen Sullivan – color graffiti added

to them by Pete.

*

*